You’d think experiencing hardship and prejudice due to your ethnic identity or nationality would make you more tolerant or sympathetic to a group of people in your midst encountering these. Especially if the differences between you are slight — so that the world sees you as sharing more similarities than differences.

The Irish have had more than their share of hardship and tragedy — from invasion by Cromwell in the 18th Century to rebellion and the more recent Troubles. As Yeats wrote:

Out of Ireland have we come.

Great hatred, little room,

Maimed us at the start.1

Ironically, now the Irish themselves – some of them, anyway — lack sympathy with a group among them who call themselves the Travelers.

The Travelers are not Gypsies, or Roma. They are a distinct group that has existed for hundreds of years throughout Ireland and Great Britain. (One group made its way to South Carolina.) They have strong family connections, and have made their their living traditionally as itinerant tinkers, traveling from town to town repairing small items. Sometimes by stealing. They are a small group, ethnically distinct by one definition; maybe not so much by another. They use their own language, Cant, which at times their hosts proposed to outlaw, as was tried with Welsh and Gaelic. Given their small numbers, the Travelers seem not worthy of much attention by international groups and individuals (government officials, reporters, ‘advocates’). One thing’s clear: no one in Ireland seems to want them in their backyard.

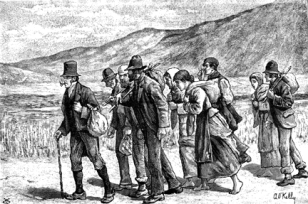

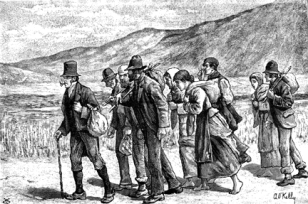

Bridget O’Donnel and her starving children, 1849, Illustrated London News

In October the New York Times reported a fire that killed ten people in a Travelers’ encampment in Carrickmines, Ireland, near Dublin. The dead included five children and a pregnant woman. The town – with a name redolent of Irish labor and suffering – contains a fragment of an ancient castle built to protect the invading English from marauding Irish tribes. (It was subsequently used as a piggery.) Encampment, summons up associations ancient and more recent — from Celtic nomads, to the Irish monks setting sail to the Shetland Islands and Scandinavia and (possibly to America) in curraghs, to Famine ships carrying human cargo, and now Syrian refugees fleeing to Hungary and Germany.

Following the destruction of the fire in Carrickmines and shock of their fellow Travelers’ deaths, the survivors sought a new location to settle. Those in the surrounding community who at first expressed sympathy refused to extend that sympathy to allowing Travelers a place to live. Local residents in Dublin blocked access to a temporary location being prepared for them.

No doubt the situation is complex. How do you create a inclusive community with those who stubbornly refuse to assimilate – who are in fact perceived as a threat? But this has always been the case. In America the dance of assimilation bred as much intolerance as tolerance as each group of immigrants made its way. The Irish showed little sympathy to Italian and Slovak immigrants. Neither group sympathized much with African Americans’ struggle for freedom and equality. 19th-century illustrations by Thomas Nast depicted Irish immigrants as violent, apelike savages.

Political cartoons during the Red Scare of the 1920s characterized Eastern European and other immigrants as bomb-wielding radicals and Bolshies. In the 1950s McCarthy-era rhetoric charged ‘fellow travelers’ as consorting with communists bent on the destruction of American democracy – which some were. It’s a short leap to the terrorists of today.

My own family, illiterate coal miners who ranged between Edinburgh and Belfast, arrived in the U.S. before the First World War. They traveled to Indiana to mine coal and then to Pittsburgh, where my grandmother was born in 1909. She was the first in her family to attend college and became an elementary school teacher – a vocation my own daughter follows.

The Irish have always been travelers, great fighters, and great laborers, willing to take the dirty, dangerous work that others would not, and live in dirty, dangerous places. I have seen their handiwork and witnessed their graves on my own travels cycling and canoeing the Erie and C&O Canals.

In 1844 I arrived upon the fateful shore.

I left the land that was no more

To work upon the railway

Cemetery at Adams Basin on the Erie Canal (Photo by the Author)

The truth is we are all travelers, making our way existentially and physically through the world, seeking a home. It’s clear from recent events that some pursue their journey less benignly than others.

Articles in the Irish Times have highlighted entrenched attitudes about the Travelers: among these that they are antisocial criminals, that they are uneducated. Money allocated to create settlements for Travelers remains unspent to opposition from their fellow Irish. One resident near Dublin said, “They just don’t live the same way we do….That’s not a slant on them. It’s just a fact.” “We just don’t want them here,” and, “No one in the country would accept this.”

These 21st-Century words echo those heard and published during the 19th Century. The Great Famine of the 1840s and ’50s, The Great Hunger – An Gorta Mor — killed thousands and sent millions fleeing to American, Canada, New Zealand and other countries. In Great Britain the general attitude was good riddance to their strange ways and tragic lives – contributed to by Britain’s own poor laws and policies of discrimination dating from Cromwell’s day.

As Cecil Woodham-Smith writes in The Great Hunger:

As Cecil Woodham-Smith writes in The Great Hunger:

The wretched, ragged crowds provoked irritation, heightened by the traditional English antipathy toward the native Irish. … “No attempt was made to explain the catastrophe to the people; on the contrary, government officials and relief committee members treated the destitute with impatience and contempt.”

No doubt my ancestors and their acquaintances were among those discriminated against. In America they were met with political cartoons and rhetoric emphasizing their antisocial behavior, their ignorance, profligacy, religion, language, criminality and otherness.

Now we witness refugees fleeing Syria and the Travelers in Ireland seeking a home. Questions of  immigration policy arise once again in the long-winded rhetoric surrounding the windup to the U.S. Presidential election, fanned by the horrific scenes perpetrated on Friday November 13th in Paris.

immigration policy arise once again in the long-winded rhetoric surrounding the windup to the U.S. Presidential election, fanned by the horrific scenes perpetrated on Friday November 13th in Paris.

Nevertheless, I am struck by the minute degrees separation that alienate rather than bind us as human beings. In the 1840s The Illustrated London News published accounts uncharacteristically sympathetic to the Irish. One article quoted an eyewitness to their suffering who declared Everything has been tried but a little sympathy and kindness. But how do you maintain sympathy for someone you’re afraid, rightly or wrongly, is trying to kill you? — CDL